Questions & Reflections – Why Comics?

July 2, 2016

I was recently asked these questions at a comics fair:

• How did you get your start in comics? What was it about the medium that attracted you (as both a creator and a reader)? What is it about the medium that makes it an effective form of storytelling for you?

I approached comics as a medium of self-determination, healing, and critical thinking. I was initially attracted to comics due to its accessibility and the possibilities that the relationship between words and images opens up for my memories. I want to remember things differently. I want to challenge our practices of recognition from ground up. I want to explore other life-affirming ways we can be in relationship with one another. I dwell on the nonlinearity of the medium and enjoy creating multiple entry points for others to engage with my content—maybe through character design, drawings, visual storytelling aesthetics, emotional resonance, etc. I use humor to establish a sense of agency, to decenter dominant narratives (immigration, trans embodiment, queer of color identity politics, community activism, etc), and most importantly to render the space of margins as inhabitable and empowering. I’m using comics to build community in tangible ways—drawing people into participating in my struggle and also for me to participate in theirs. This is how I imagine the healing process and stage a paradigm shift.

• How would you describe your work? What do you hope people take away from it? What is your goal with your work?

I consider most of my comics some form of graphic memoir, because I use my emotional truth as a starting point of exploration and engagement. I use visual storytelling as a platform to think critically. Also, my work is very much manga-inspired, since I’m drawn to the nonlinear visual storytelling of manga. There are many instances where I disrupt the normative left-to-right reading order by breaking panel borders and forcing the reader to move their eyes around the page. For Memory of an Avalanche particularly, the storytelling style is a bit choppy and works like an emotional rollercoaster. That’s because I use the concept of impossibility as an organizing principle of the entire graphic memoir, as a way to articulate the inarticulable violence, which is the lived reality of those inhabiting multiple margins. I’m using this storytelling style to disrupt romanticized narratives of survival (e.g., marriage, citizenship, graduation, etc) and disorient the reader from what they’re usually comfortable with. I’m strategically (and literally) opening up the “in-between” space, the spatiotemporal location between “before” and “after,” and to resignify what markers of “survival” and “success” mean via both form and content.

• What role do you think comics fairs play in the larger comic industry? How was your experience tabling at these events (what was the reception like from people who saw your work there)?

It’s always been very life-affirming to experience people interacting with my work—to pick up the comics and flip through them. That’s very meaningful for me. I feel that people are generally very supportive of my work, which I’m absolutely grateful for. There’s always an element of surprise when showing my work to the public, of finding unexpected readers and accomplices. I really dig that, especially when people laugh and get my humor.

Memory of an Avalanche Q&A

December 17, 2015

Last month Ikaika Gleisberg and Rebekah Edwards kindly invited me to present on Memory of an Avalanche in their Foundations in Critical Studies: Embodiment class at the California College of the Arts. Below are my responses to some of the questions from the class…

• WHY COMICS?

I found comics to be a good medium of connection due to its accessibility. I’m interested in the possibilities that the relationship between words and images opens up for this narrative. I want to create multiple entry points for others to engage with the content—maybe through character design, drawings, shojo manga aesthetics, emotional resonance, etc. I want to exploit humor to establish a sense of agency, to decenter dominant narratives (immigration, trans embodiment, queer of color identity politics, community activism, etc), and most importantly to render the space of margins as inhabitable and empowering. I’m using comics to build community in tangible ways and to draw people into participating in my struggle. This is how I imagine the healing process and initiate a paradigm shift.

• WHY GRAPHIC MEMOIR?

I’m using the illusion of truth often associated with the genre of graphic memoir to instigate discomfort and validate the existence of margins. However, while I’m categorizing my work as a graphic memoir for others to take this narrative seriously, at the same time I’m disrupting this very dichotomy of truth VS lies, questioning the significance of that distinction in processes of identity construction and relational practices. The content of my work challenges this truth-lie dichotomy by poking fun at the audience’s curiosity itself. If one is wondering whether or not any part of my narrative is true, they are, in the logic of the story, rendering themself a cultural authority—akin to the court clerk, the immigration officer, or the doctor who constantly questions the legitimacy of the protagonist’s identity and existence (i.e., “Is Bo a good or bad immigrant?”). So in a sense, I’m using the “graphic memoir” genre as a two-pronged approach—to normalize the existence of margins and to subvert the cultural conditions that create and maintain those very margins.

• MY STYLE

My work is very much manga-inspired. I’m drawn to the nonlinear modality of visual storytelling in manga. There are many instances where I disrupt the normative left-to-right reading order by breaking panel borders and forcing the reader to move their eyes around the page. That’s another way I’m enhancing this aspect of emotional truth. In terms of the drawing, I feel that comics is an art of abstraction. One rule I have for abstracting my characters is that they must in some way remain racially recognizable (or strategically unrecognizable) as well as legible in terms of gender embodiment. I spend a lot of time on background work, which is typical of most manga, since I want to build a world that’s comprehensible and relatable, to exaggerate the illusion of truth. In terms of the storytelling style, my comic is a bit choppy and works like an emotional rollercoaster. That’s because I use the concept of impossibility as an organizing principle of the entire graphic memoir, as a way to articulate the inarticulable violence, which is the lived reality of those inhabiting multiple margins. I’m using this storytelling style to disrupt romanticized narratives of survival (e.g., marriage, citizenship, graduation, etc) and disorient the reader from what they’re usually comfortable with. I’m strategically (and literally) opening up the “in-between” space, the spatiotemporal location between “before” and “after,” and to resignify what markers of “survival” and “success” mean via both form and content.

Memory of an Avalanche – Dissected

June 3, 2015

Here’s a closer look at the Dissected sequence I just finished. All the art is hand drawn & inked, and the lettering is done in Photoshop. I decided to avoid pre-made screentones this time around and draw all the textures and emanatas (visual effects) by hand. Lots of work but worth it. I went back to manga how-to books from good old days and practiced lots of cross-hatching and speedlines. I also had to learn how to do digital lettering from scratch despite school computer lab nightmares and limited equipment access.

This scene takes place exactly one year before DOMA was struck down, where only “opposite-sex” marriages were allowed in California and subsequently qualified for immigration benefits. The protagonist and his partner are trying to pass as an “opposite-sex” couple to get married—first step in the game of marriage petition for permanent residency.

Memory of an Avalanche – Refractions – Behind the Scenes

May 13, 2015

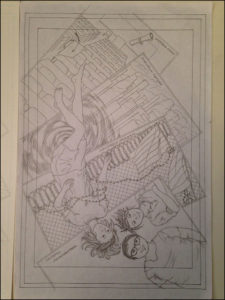

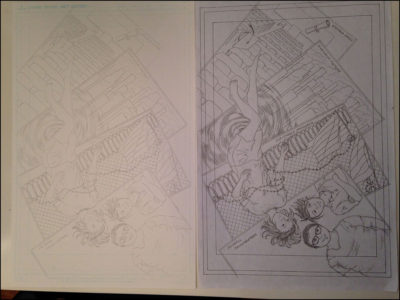

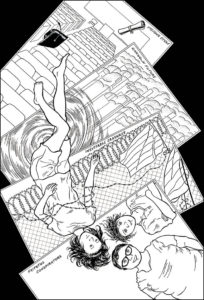

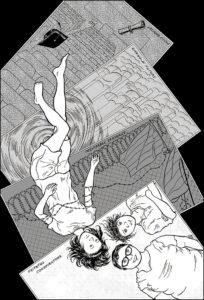

I have been wanting to share the images of my work process. Here are some from “Refractions,” a potential cover of my graphic memoir Memory of an Avalanche. It’s a multi-step process—I generally do everything by hand up to the post-production stage. This piece was essentially made for a “compression” assignment, where the entire story must be told within the space of one page: 4 panels with 2 words of narration per each.

So I began by working out the concepts and compositions, heavily referencing the figures and backgrounds, doing a tight sketch, transferring the sketch onto a good comics paper (11 x 17″), then inking the whole thing by hand (brushes for large, organic areas and dip pen for details). Afterwards, I scanned the inked work and applied digital screentones, which are patterns of lines and dots commonly used in Japanese manga.

How can “invisible” forms of violence be visually represented? Is it even possible? My main challenge was to articulate the simultaneity of intersectional oppressions in a visually recognizable format. Of course representing the entire story, the inarticulable trauma, and the visceral effects of border enforcement within the structure of linear temporality was an impossible task. But reckoning with this condition of impossibility was a starting point to come up with my own ethics of representation.

One of the readers mentioned that they read the piece as the protagonist traversing (or falling through the cracks of) multiple institutional spaces, and that it is these very conditions of violence that precisely facilitate the possibilities of resistance, as can be seen from the interstice of accomplices in the bottom panel (protagonist’s friend and partner). Some other folks mentioned reading the rectangular panels as tarot cards, particularly because of the curious narration. Here we have the dealing of cards, the uncertainty of the protagonist’s fate, the irony of chance carefully calculated by the matrix of state and capital, like the idea of the diversity lottery visa.